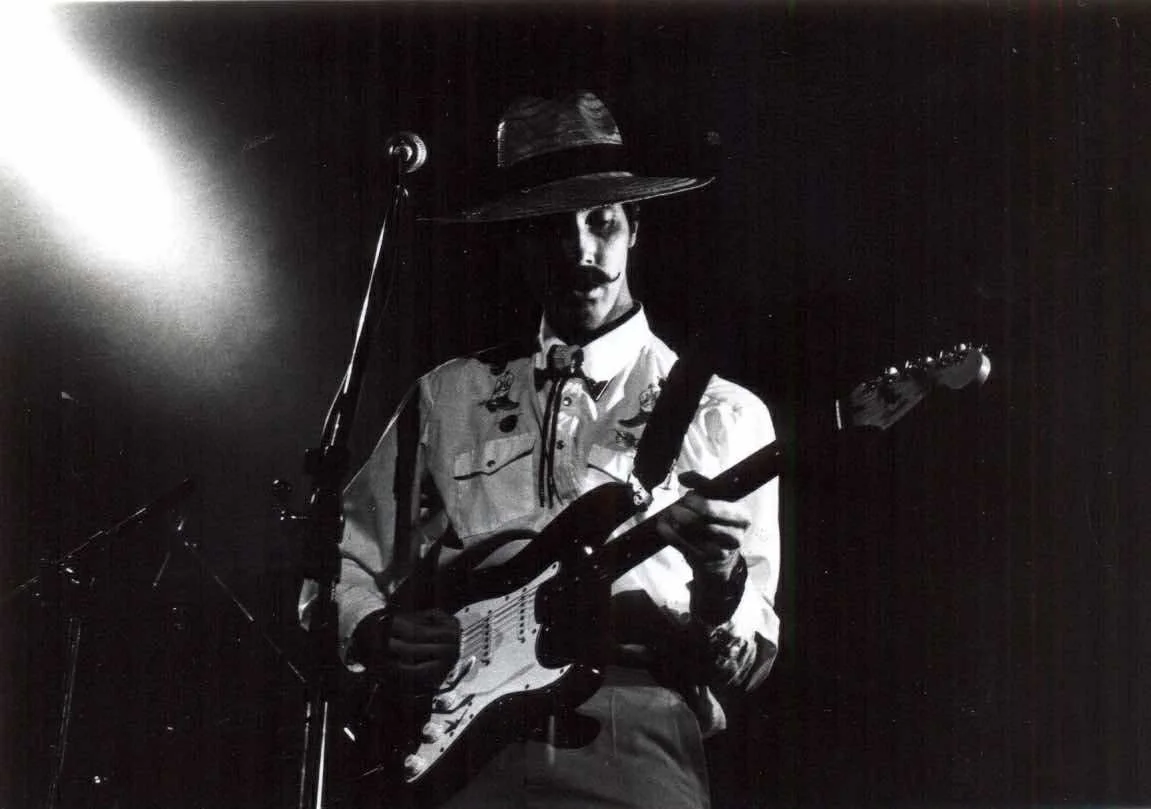

Lester Square :: The Monochrome Set Interview

Thomas W.B. Hardy, known professionally as Lester Square, is a household name within the post-punk/new wave world that took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the UK, and has since become a legend among his peers and cultural contemporaries over the last half-century. After leaving the earliest formation of Adam And The Ants, Square went on to form the highly influential The Monochrome Set with Indian-born singer-songwriter Ganesh Seshadri, whose impeccable influence inspired such groups as The Smiths, Orange Juice, and Franz Ferdinand, among others, over the years. Throughout his career, the veteran musician and visual artist has released several solo albums and regularly contributes to organizations such as TES (Times Educational Supplement), and is outspoken about the ongoing concerns of climate change and environmental extremes.

Born Thomas W.B. Hardy in Canada in the spring of 54, and eventually relocating to England, how did you initially become fascinated with music, more specifically guitar, and songwriting?

Gilbert Read, a neighbour of mine at the time, introduced me to the mind-blowing world of Jimi Hendrix when he placed speakers on either side of my head as I lay on his sofa, while playing all four sides of “Electric Ladyland” without interruption when I was 14. The effect on me was immediate. From that moment, music would become the central pleasure of my life, both listening and playing. Gilbert and I formed our first band, The Bitter End, in 1968 when I was 14, six months after buying my first guitar and learning the rudiments. We bought our instruments from a second-hand shop. I think mine was hand-made; it had been completely painted in black household gloss paint, including the neck. Our amps were single-speaker Wilsons from the 1950s. And we rehearsed in a church hall, carrying our gear back and forth on a hand cart. We carried on until I was 17. As I recall, we cut our teeth on easy blues like Spoonful, and of course, “House of the Rising Sun.” It was a stroke of luck that we lived a block away from the TW Music studio at Fulham Cross, where we hung out with Juicy Lucy and Heads Hands and Feet long before their first releases and fame. It was only much later that I realized that watching Albert Lee play informally at close quarters and picking up tips on ‘playing country’ was out of the ordinary. As fate would have it I was also in the right place at the right time when I found myself at the Isle of Wight festival in 1970 where, as a latecomer to the 60s scene, I managed to catch pretty much all of the iconic bands of the decade in one weekend: the Who, The Doors who sang ‘come on baby light my fire followed by Jimi Hendrix who amplified his legend as well as his guitar by actually setting fire to the stage. Music was central to everything. Every weekend was spent at Implosion at the Roundhouse in Camden, where DJ Jeff Dexter held court and hosted the great and good of the psychedelic underground. Love, Curved Air, Pink Fairies, Kevin Ayers, and the ubiquitous Edgar Broughton Band were highlights. Hawkwind was practically the house band.

Tell me about your time while attending Hornsey College of Art, where you met a friend and future bandmate, Stuart Leslie Goddard (Adam Ant). How did The B-Sides, an early incarnation of Adam and the Ants, first come about in the mid to late 1970s?

In 1975, I went to support Hornsey band Bazooka Joe at St Martin’s School of Art. This evening is seen in music history as a key moment in a musical paradigm shift. The support act was the debut of the Sex Pistols. Historical accounts (as well as film versions of the story) recount this as a large gig to reflect the importance of the moment. In fact, it was held in a tiny hall with an audience of a couple of dozen. Bazooka Joe's singer, Danny, was involved in a minor scuffle as these amps were in danger of being trashed. The significance for me, though, was its influence on Stuart. It was his epiphany. He wanted to do something else, which was as iconoclastic as the Pistols but in a different way. He soon left Bazooka Joe, phoned me up, and suggested we form a new band, the B-sides. The concept was that we only play the B-sides of 1960 singles that hadn't been hits in the first place: a loser’s band. This is what we told bassist Andy Warren when he joined us after answering an ad in Melody Maker, which read, “beat on the bass with the B sides.” To invent an appropriate persona, I coined the stage name Lester Square, as nerdy a name as I could muster. We called ourselves losers as a nod to the punk ethos, but with a more arty concept. Eventually, the idea became tiresome, and we started working on our own songs. My contributions included “Puerto Rican Fence Climber” (named after the winkle pickers that enabled escape in West Side Story), “Fall In", and “Fat Fun.” The last two were eventually recorded as part of the Ants canon. Stuart was one of the first people I met at Hornsey. Then he was a Marc Bolan lookalike in a double-breasted suit with wide lapels, which were the fashion at the time, and a backcombed shag hairstyle. The rock star potential was somewhat reduced with the addition of bottle-thick national health glasses. We became firm friends and shared a love of early Roxy Music, David Bowie, and early Glam Rock. He was quite shy, as I recall. In the early ‘70s, art schools were melting pots of the emerging new wave music scene. Although I attended as a painter, it was involvement in music that took over. At the time, I shared a flat in Crouch End with fellow Hornsey Art College students, including guitarist John Ellis, who then played with the Vibrators but went on to play with the Stranglers and Peter Gabriel. I had a studio in the college’s Fine Art department at Alexandra Palace with French windows overlooking Alexandra Park, and London beyond. I shared this space with Anish Kapoor, who went on to greater things. The social life of the college centred around the band Bazooka Joe, led by fellow student Danny Kleinman, who had a residency every weekend at a nearby pub. Danny became a film director and has made all the recent James Bond title sequences. Stuart joined Bazooka Joe as bass player under the name of Eddie Riff.

Having written some of the band’s most iconic tunes in the early days, did you already have an idea or vision of what would eventually become The Monochrome Set? A highly influential group that would later inspire such bands as The Smiths, Orange Juice, and several others.

When I jumped the Ants’ ship, Bid, an old school friend of Andy, and I tried out several combinations of musicians and names. We were in turn, the Ectomorphs and the Zarbies but we eventually stuck with The Monochrome Set because it occurred to me that a television, with its ability to switch between channels and was the perfect metaphor for our blending of the various musical styles that we brought to the writing: Bid loved the Velvet Underground and cabaret styles, I contributed a love of psychedelia and West Coast guitar bands. I also thought that dials on a TV set, which proclaimed “Volume”, “Contrast”, and “Brilliance” perfectly summed us up! The preamble of any press review of The Monochrome Set will inevitably comment on how difficult it is to classify the band. The mistake is to try to squeeze the band into narrow definitions; we were neither punk nor new wave. I think what made for any claim to originality we had was the creative tension between consummate musicians - Bid and Andy - and visual artists - me and Tony. And what other band of the ‘punk’ era could boast a classicist for a drummer! As a skilled guitarist, Bid's musicianship allowed for predictable structures. My interest extended to open-ended experimentation, building upon accident. standing back, considering, carving away, and sculpting the sound. That’s not to say that I didn’t have an ear for a good guitar hook! I think my melodic counterpoints to Bid’s vocals became an essential element to the sound and one thing that set us apart from the stripped-back punk sound. However, we were very inward-looking, and it fascinates me how often, in our case, artists themselves may not be aware of the wider implications of their work and the influence it might have had on other bands.

There have been several members over the decades, but I’m curious as to how you initially met the band’s earliest collaborators like Bid (Ganesh Seshadri), John D. Haney, Charlie X, Jeremy Harrington, Simon Croft, Andy Warren (The Ants), and Tony Potts (Fifth Member). Having released several sonic singles for the mighty Rough Trade before the band’s iconic 1980 debut “Strange Boutique,” what was most important for you to achieve and express with this particular body of work right out the gate?

As I said, Bid was a friend of Andy that we roped in when Stuart had a breakdown and the B-Sides folded. We also roped in Dorothy Max, another friend of Andy who played drums before going on to work with Throbbing Gristle. Adam eventually emerged again, and Andy and I joined the first version of the Ants. I later left to finish my fine art course. Then Bid and I put together the band that eventually became the Monochrome Set, stealing John Haney from The Art Attax and eventually Jeremy Harrington from Gloria Mundi. Tony Potts was a friend of John who studied film at the Central School of Art. I can’t remember how we met Simon and Charlie, although Simon and I reconnected later, and his production skills were helpful as my solo work progressed. My time at art school coincided with the dying throes of antiseptic modernism and the birth of The Monochrome Set sat almost exactly on the threshold of the iconoclastic Postmodern era. In retrospect, in tune with postmodernism, our interest lay in exploring the eclecticism of our various inputs: the deconstruction of expected genres, the unashamed appropriation and juxtaposition of disparate elements from every corner of musical history, a lack of respect for accepted canons, and a collaborative approach which, I think, led to us becoming more than the sum of our parts. Modernism had its dying fling with the conceptual Art and Language group. Unfortunately, it was an associate of the Art and Language Group, Mayo Thompson, who was assigned to produce our first single for Rough Trade. His instruction to strip back all counterpoint, harmony, rhythm, or hint of influence was in tune with the dying ethos of Modernism, but, given all of the above, it was anathema to us. No matter how much attention the debut received, we weren’t satisfied with the results. We quickly followed the album with our demo version (produced by John Ellis) on our own label to guarantee our first release revealed the band as we wanted to be seen.

This album is a tonal trailblazer for the upcoming New Wave movement. What do you recall about the overall experience of bringing this collection of material to life? What ultimately led to your decision to leave the band along with Lexington Crane in ‘82 shortly after the release of the group’s third record, “Eligible Bachelors”, and eventually joining other acts such as The Invisible, …And the Native Hipsters, and Jesus Couldn’t Drum?

We had recorded several sessions for John Peel’s Radio One shows when our producer was Bob Sargeant. This time, it was the right fit, and Din Disc employed him to work on the “Strange Boutique.” His expertise polished our particular sound and made it more accessible to a wider audience (the multitracked Burundi drumming at the start was emulated on the Ants’ music release later that year). It was recorded in an old-style by playing the songs live and then overdubbing where we felt free to experiment. The fairground carousel sample in the middle of “Goodbye Joe” is one example. Another is the wild free-form guitar soloing at the end of the song “Strange Boutique,” which was geared to contrast with the sixties-style keyboard sound of the rest of the song. We also dropped the bass to subsonic levels for no particular reason. I left because I wanted to go back to college, and touring was impractical, so I missed out on “Lost Weekend.” I did, however, during that time, put together The Invisible, a band for recording only, which included my then-girlfriend Carla Mandy and fellow Canadian Phil Staines on Drums. We drafted in Paul Nesbitt from Gretchen Hofner, but needed singers. I think we met up through an advertisement. Chris and David were songwriters whose specialty was tight harmonies, with songs that had no introductions, middle 8s, or any structure beyond the vocal parts. I worked up the songs with them, adding instrumental passages and arranging musical counterpoints. I had known Pat Collier from his days with the Vibrators; he had since become a sought-after power pop producer and agreed to produce the album. It was, at the time, an invigorating exercise in expressing all the over-the-top psychedelic excesses that were too extreme for the Set at the time. I was pleased when one review said that, “it sounded like it had been produced by people who had been locked in a room and forced to listen to nothing but ‘Rain’ by the Beatles for their formative years!” And the Native Hipsters have asked me over the years to contribute guitar parts for their musical collages, and Jesus Couldn’t Drum asked me to guest on and produce their album. So, I was not really a band member in either. The Monochrome Set split up soon after “Lost Weekend,” but in 1990, we had an offer to reform and tour Japan as a new generation of fans had emerged. We eventually toured Japan four times and had a few short visits to Tokyo, as the fan base remained solid. I eventually recorded 13 studio albums with the band, but left again in 2013 when I broke my ankle and decided I needed to devote more time to my young children.

I’m curious to know how a young man in the prime of his creative career navigated the societal shifts and political nature of the 1980s, while remaining monumentally motivated, curious, and disciplined in your craft. As a multi-disciplinary artist who’s released several solo albums, soundtracks, and has become a driving force for TES, QCDA, MDE, etc., what inspires you the most after nearly half a century working in the arts? What have you been up to most recently, and is there anything else you would like to share further with the readers?

Motivated and curious, yes, but I wouldn’t say I was disciplined at all. Most of my career was spent being in the right place at the right time. I was never as disciplined, technically proficient, or an instrumentalist as Bid or Andy. I regarded the guitar as a means to write melodies and experiment with, not to gather a repertoire or pursue the skill for its own sake. I originally wanted to play like Hendrix, but in failing, I came to terms with the simpler twangs, which became my ‘go-to’ sound. As for societal shifts, we worked in our own bubble, and not much outside impinged on our world. My overwhelming concern now is the environment and sounding the alarm about the need to address the impending climate disaster. There is nothing more important to me than this, but I manage to decompress by occasionally painting and composing music. I have released nine solo albums since leaving the band. I have a new album ready for release early in the new year. It is called “Sin,” and it is a collection of my poetry set to musical soundscapes. Check it out on Bandcamp.