The David Chesworth Interview

When and where were you born? When did you first begin to fall in love with music, more specifically synthesizers? Was music relevant around your household growing up? Do you have any siblings? Who were some of your earliest influences in your more formative years? When and where did you see your first show and what ultimately inspired you to pursue a life in music and art?

I was born in England and moved to Melbourne Australia with my parents when I was 11. I was always into music, but never properly learned how to play an instrument. I tried to learn guitar and taught myself piano because there was one in the house. Both parents were into music. My mum sang in a choir and played piano and both my brothers played instruments. I always loved pop music but was also exposed to Western classical music as this was often played at the school I was at in England, during assembly and sometimes just in listening sessions. We lived in a small town called Alsager, near industrial Stoke-on-Trent. One memory I have is there was a church half a mile away which used to rehearse bell-ringing twice a week and it would go from about 8-10pm and as a young child I would lie in bed listening quite intently to these bells. Just taking them in. I was intrigued by them because of their patterns. Bell ringing was like minimalist music that I would encounter later, where there were patterns in various permutations and remembering those patterns is a skill in different bell-ringing groups and churches throughout England. I used to listen to this twice a week for two hours of intensive listening, which influenced my enjoyment of simple structures and the consequences of different rhythmic and melodic collisions.

1979 saw the release of your debut album “50 Synthesizer Greats” on the label Innocent. Tell me about writing and recording this record and what you ultimately wanted to achieve and express with this material.

“50 Synthesizer Greats” came about as a playful exploration that kind of commented on all the music that surrounded me in 1978. There was no intention of releasing it as a record, rather it was done for my own gratification. My career began, toiling away on my summer holidays of 1978/79 in Melbourne in a suburban hut: an industrial microcosm surrounded by noxious polymers. For, my dad had a friend who had a tiny printing press. He’d also make things out of Bakelite, as well as a machine that extruded little plastic hi-fi knobs. I was put on the Bakelite and knobs machine – all day. It was a terrible job because there was no one to talk to. They had this radio station playing all day, which used to play ‘beautiful music”. For 8 hours a day I had little choice, but to put up with the stifling compositions of Bert Keaumpfert, 101 Strings and lesser entertainers, plus ads. This proved to be interesting for the first hour only! Enduring the smelly and mind-numbing time in the factory, I had scraped together enough cash to purchase a domestic reel-to-reel tape recorder and borrowed a friend’s Mini Korg 700 synth. Each night, after working, I would set up on the parent’s kitchen table and noodle away on the synth, recording several layers of music building up each of the 50 pieces. At first, I was reluctant to share the music, but I played 38 of the best tracks to my friend, Philip Brophy from the group Tsk Tsk Tsk. He convinced me to try and release it myself, which wasn’t easy to do in those days.

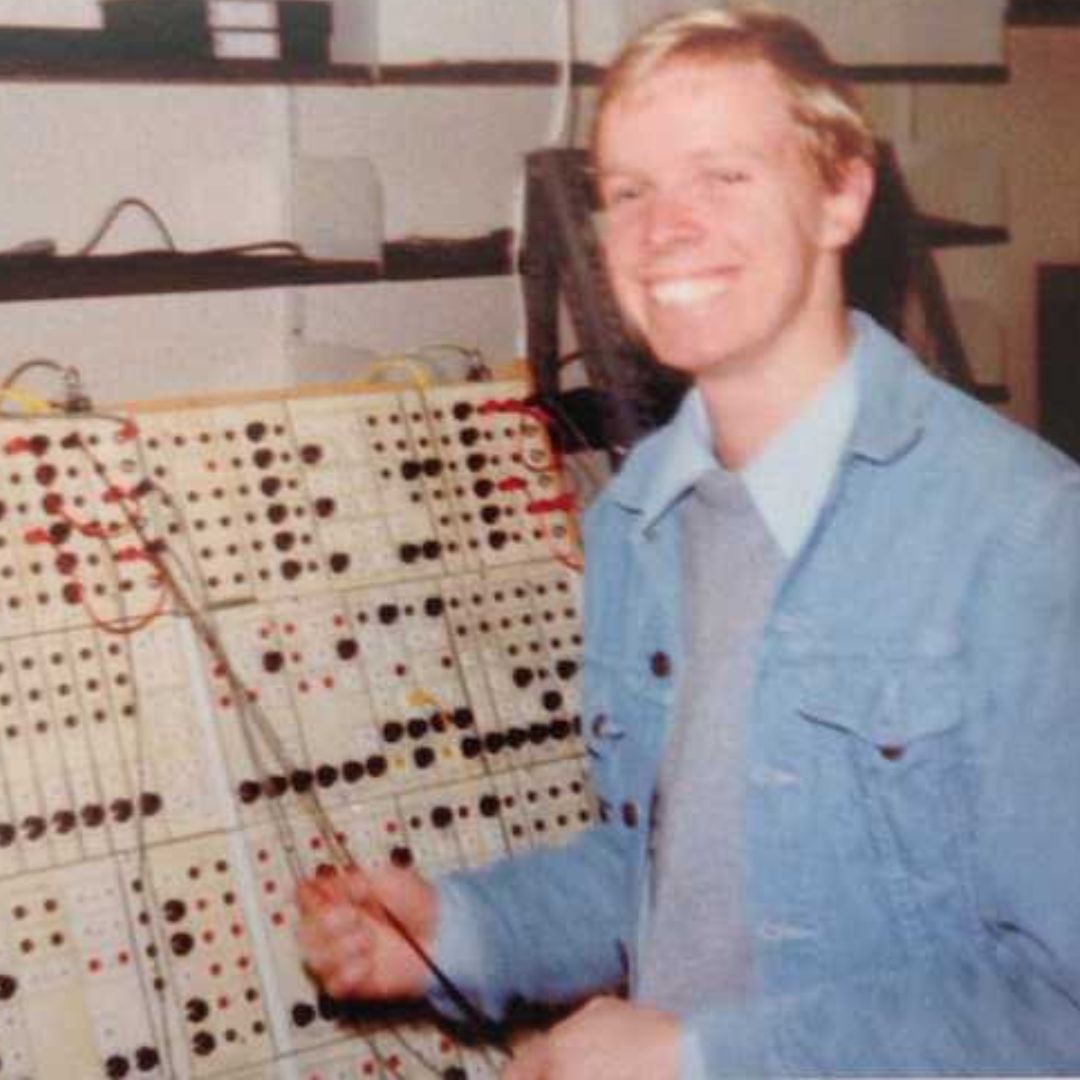

One way to approach this eclectic collection of pieces is as a cynical take on the popular music at the time. There was a popular record label called K-Tel and they used to package compilations called ‘20 Love Songs’, ‘20 Classical Romantic Tunes’ and so “50 Synthesizer Greats” was put together to mock that idea. Philip and then partner Maria Kozic were also visual designers and created the cover with the cheesy (then, hi-tech) picture of myself grinning which we screen-printed ourselves. By this time, I was a student at La Trobe University Music Department, which taught a progressive music curriculum to non-specialized students. I gradually taught myself how to use the department’s 8-track recording studio. Over a couple of years, I recorded and mixed many of the releases on our new label Innocent Records (ran with Tsk Tsk Tsk’s Philip Brophy) working ‘under the radar’ at night and on weekends. With the 8-track recorder I was able to layer up to 20 tracks by bouncing the initial 8 tracks to a stereo mix on a separate tape recorder and then laying that mix back onto the 8-track recorder. I then added more tracks to the 6 tracks that had become available again. I did this up to three times as I built up the layers. This meant that there was never any going back to fix earlier tracks because they were now mixed in. (I also used this recording method on my first record, “50 Synthesizer Greats”, although in that case I only had access to a domestic two track recorder to layer up sounds at home.)

You released your follow up, “Layer on Layer”, in ‘81. What was the overall approach to this record now that you had some experience under your belt? I’d love to know some of the backstory and inspiration for songs like “The Bits That Move Together”, “No Voices”, “Thoughtful Food” and “Power”.

There are many found and makeshift instruments used in the “Layer on Layer” recording: some percussive and unpitched, and others pitched, although they were not necessarily tuned to any ‘correct pitch’ whereby the ‘out-of-tuneness’ lent the sound a particular quality. Much of the percussion was produced by hitting thick telephone directories, books, metal objects and a range of resonators derived from everyday objects. The first track “Thoughtful Food” features a metal anklung, a southeast Asian rhythmic instrument consisting of a set of bamboo tubes. In this case they were made of metal as they were made especially for the avant-garde composer Keith Humble (who was the instigator of the music department). The anklung tubes are tuned in octaves and slide in the grooves of a frame shaken by the performer. The main tom-like drum sound is derived from cheap Chinese stretched silken hand fan that I hit with a small beater close to the mike. In the background can be heard odd, out-of-tune synth chords, which were crudely shifted on an early digital pitch shifter. The Mini-Kong 700 was possibly used on this track too. Track 2, “Who’s asking” features a rhythm track built-up using simple number games to work out patterns of occurrence. This technique is also used on “Lost in Madagascar”, the B side to Essendon Airport’s “Talking to Cleopatra” single, which was being recorded around this time too. Also featuring on the track is the rhythmically and tonally odd guitar playing of Robert Goodge (Essendon Airport). “Music Speaks” self-referential lyrics call into question the expressive qualities and conceptual conceits often present in music-making. Also, stylistically, the track is a nod to Talking Head’s

Remain in Light”, which had recently been released. Again, in this track, I employed a kind of jigsaw puzzle approach where different number patterns were employed to layer up a sonic accompaniment that filled in all the available gaps.

“The Bits That Move Together” was created starting from an echoing synth tape loop which is heard at the start. This provides the framework off which all the music hangs. You can also hear Robert Goodge’s guitar playing and Tch Tch Tch member Ralph Traviato’s saxophone. Ralph, together with other Tch Tch Tch members, Philip Brophy, Jayne Stevenson and Maria Kozic, provide the backing vocals. I have always been spilt between a pop aesthetic and more experimental music making. “Power”, first track on side two, was made using a Serge Tcherepnin Modular Synthesizer controlled by Daisy (an early CV Generator/Sequencer system) that was installed in the Latrobe music department studio. The output was processed through a digital delay unit. These devices were just becoming available. This one was built from a kit by studio technician Jim Sosnin. It added a symphonic-like timbre to the raw electronic sounds. The pitched, tinkling, percussive sounds are from a toy rattle that I closely miked. “When The Beats Meet” was made by sending acoustic guitar chords into a Serge Tcherepnin Modular Synthesizer, where they were gated and filtered, resulting in interesting unnatural percussive rhythmic effects. Guitarist Robert Goodge moving an electric shaver across the bridge of his electric guitar created some of the sounds in the final track, “No Voices”. Over this, I played sounds from the newly released Casio VL-Tone keyboard. Additional sounds were also added and processed but it’s too long ago to remember exactly what they were. The drum machine at the end of the track was pre-existing on the audio tape that I was reusing and was kept. These audio ‘accidents’ can be interesting compositional elements sometimes worth incorporating.

You are a very prolific artist and have continued to create and release music over the decades with albums such as “No Particular Place”, “Tantrum”, “Wicked Voice” and so many others. What is most important to you when creating music and art, especially as you get older and everything changes? What keeps you inspired, driven and determined year after year?

I was always curious about why an artist’s music often changes as they get older and now I am finding out why.… Your peer group disappears, music changes around you, new technologies emerge and what was once creatively important in music is no longer the case. Although another way to look at this is that people have time to grow into your music and discover ways in which it operates that’s not the case in other music. I tried my best to play my music as best I could, but was always more interested in getting the idea down rather than getting the technique right. This foreshadowed the idea that one’s musical competency and questionable ability imparted endearing musical qualities. My questionable dexterity has served me well!

What have you got in the works for 2024 as we close out yet another year on this humble marble? Is there anything else you would like to further share with the readers?

I am a busy video and installation artist these days, so I have a lot on. As a musician though, I’m not sure what’s ahead, however I am performing again with my post-punk minimalist group Essendon Airport. Last year, I toured Europe with solo presentations of “50 Synthesizer Greats” and “Layer on Layer” which was very successful. I’d love to tour these to the states too, if I can arrange some dates. Plus, I have a couple of recent recordings that I would love to release. I can send those to any label that might be interested in hearing them.