Roland Brultey - Rictus Interview

Tell me about growing up in Luxeuil les Bains (France). What were those early like for you?

I was born in December, 1954 in a small village near Strasburg, and moved to the Luxeuil area as a teen. My family had peasant roots but had achieved middle class status by the 1960s; I grew up quite happy. It was the beginning of the famous sixties, but one shouldn’t believe we had any sort of awareness of what it would mean to people today musically speaking. I didn’t grow up in a musicians’ family and neither did my childhood friends; music was not really part of people’s lives apart from a couple of radio hits and a few traditional songs passed down from generation to generation. At that time, FM radio didn’t exist in France and only three LW stations were available. They only aired French music and as kids, we never questioned it. As a ten-year-old, I listened to “Hit Parade” shows that featured the bubblegum pop of Johnny Hallyday, Claude François, Sylvie Vartan, or Sheila—a style ironically labeled “Yéyé” by French journalists of the time, puzzled by the singers’ insistence on screaming “yeah yeah” during their performances. When we started middle school, I made new friends who introduced me to rock bands: the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Bee Gees, the Beach Boys, and a little later, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Lou Reed, Genesis, and many more. Some teachers also listened to them and it quickly piqued my interest—my friends and I started buying their records, feeling a bit like rebels!

When did you first begin playing music?

I was 7 when I started taking piano lessons with Ms. Juliette Portman. One may wonder why, considering my family background. It is way later that my dad actually told me why he had decided to have me take lessons—he explained that when I was around 4 or 5, he and my mother had brought me one afternoon to a pub in which an accordion player was entertaining the patrons. He said that we spent three hours in there and I stood in front of that musician wiggling my fingers in the air, pretending to play the whole time. I even started crying and threw a huge tantrum when we left before the end of the show! We went back again to that place some time later, and I did the exact same thing. That time, the accordionist came to speak to my parents and told them: “your son definitely has to play music—I’m convinced he’ll be great at it.” So I started learning with Ms. Portman at the age of 7. Her approach was very old school, and I didn’t get to touch the piano until I had done music theory for a whole year. Frankly, I had to force myself to go there—I hated every second of it. But there was no other choice, as it was that or nothing.

I understand you started playing the piano as well as the accordion at an early age. Was music something that was relevant in your household growing up?

When I was 8, Santa Claus left an accordion under the Christmas tree. I had never held an accordion in my life, and the piano lessons were still purely theoretical. I personally don’t have any clear memory of it, but my parents liked to boast that barely two hours after I had been gifted the accordion I had played “Silent Night” to them perfectly! I think my parents were proud of the fact I played the piano as it was considered the instrument of a social class way above ours. But the part they probably truly enjoyed was when I played the accordion at home, so they could dance to the waltzes, tangos, or paso-doble themes of their youth.

What inspired you to purchase your first guitar at age 15? Who were some of your influences early on?

Growing up, I continued to play and learn the piano and the accordion. Classical piano, taught through classical methods and exercises. But when I was going out with my friends, some of them sang current hits, accompanying themselves on the acoustic guitar. Given how successful they were with girls, I quickly wanted to do it too! Until I started writing and composing my own music, I can’t really talk about influences. From the age of 15 onwards, I got more and more into British and American rock bands and singers: Jimmy Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jethro Tull. As to French music, one band that I absolutely loved and still respect immensely to this day was Ange (especially their first four records.)

Where would you go to see shows in your community and what groups/performances stood out to you the most during that time? What would you and your friends do for fun back in the day?

I’m not sure that your US-based readers can truly understand the fact there wasn’t anything to see in our lost region in the deep countryside! In order to attend an actual music show you had to travel to a big city, and the closest was over 60 miles away. That’s what we ended up doing when some of my friends were old enough to drive, in the early 1970s. I can clearly remember my first musical slap in the face: it was an Ange concert. I was stunned both by the sheer power of their music and the stage presence of the lead singer, Christian Décamps. We would often go to Saturday evening “bals” in the region. A “bal” was a musical event organized in a large frame tent that moved from village to village every weekend. The music was provided by an “orchestre de bal” that performed covers of current hits. Orchestras didn’t all have the same setlist, and they were constantly changing: as the youth started listening to more and more British and American music, some orchestras started playing less and less French variety. While most of them were composed of five or six amateur musicians, some orchestras became almost professional, boasting over ten musicians and featuring a brass section and backing vocalists. A larger band could play covers of James Brown or Chicago (I remember going crazy over “25 or 6 to 4” on a Sunday afternoon.) A smaller one, like the band Caligulas, would cover “Race with the Devil” by The Gun or “Gloria” by Them—two fantastic songs I had never heard before and discovered at a “bal!”

Prior to Rictus, you were in a band called ‘Secession’? Can you tell me about this group and how you guys came to be?

Secession was one of those smaller orchestras that played in the region when I was a teenager. I remember going to see them play with my friends at Saturday evenings “bals” in our area. They were more sixties-oriented and played songs by Chuck Berry, Bill Haley, Carl Perkins, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, and a lot of Shadows songs. They always opened and closed their show with Shadoogie! They also played some French songs by the “Chaussettes Noires” and the “Chats Sauvages,” two bands that played French adaptations of British and American hit songs. Traditionally, both small and big orchestras enlivened the evening by devoting half of their repertoire to bal-musette music: we’re talking waltzes, paso-doble, javas, tangos, and fox-trots. One has to bear in mind that the raison d’être of those “bals” had always been the dancing. We’re talking about a variety of partner dances that allowed possibly romantic encounters (“bals” were basically the only place where young men and women could hold a partner in their arms without anybody giving them the stink eye.) I’ve been told that for Americans those dances are seen as a part of the “French way of life.” They definitely were at the time! Secession featured Daniel Corbont on bass guitar, accordion and vocals; François Corbont on the drums and providing backing vocal; Paul Benoît on lead guitar, organ, and providing vocals; and Gérard Salvaty on rhythm guitar and providing backing vocals. One Saturday evening, I was attending one of their shows with my friends when my best buddy Jean-Pierre Defer told me that they were looking for somebody to cover for Gérard Salvaty, who wanted to take a month-long vacation. I was barely seventeen and had never even touched an electric guitar—only an acoustic one! Jean-Pierre was very persuasive and a few days later I was playing Salvati’s guitar, a Fender Telecaster. I quickly learned the setlist and how to handle the electric guitar, and Daniel Corbont took me onboard. I ended up playing with Secession the whole of August 1972.

I understand you guys played popular covers in local clubs. It was around this time you began to really harness your craft learning multiple instruments. Can you tell me about those early days of playing gigs and being amongst a live audience?

I loved being on stage and playing in front of an audience that genuinely enjoyed our music. I had been adopted immediately, both by the audience and my fellow musicians, who were all older than me by at least six or eight years. The return of Gérard at the end of August hit very hard for me. Everybody went back to their original spot: him on stage, and me among the audience. When I heard him play the opening theme (Shadoogie, that I had been playing many times myself), I couldn’t hold my tears. I was standing ramrod straight, arms crossed, the seemingly unstoppable tears rolling down my cheeks. I thought everything was over—how wrong was I! Daniel Corbont and I got on really well during that one-month period and remained fairly close after Gérard’s return. Everything had gone so fast that he wasn’t aware that the guitar wasn’t my main instrument—and he definitely didn’t know that it was the instrument I played with the least amount of skill. Guess what, Daniel: I’ve also been playing the piano and the accordion since I was 7! As the band leader, Daniel asked the company that hired Secession to play at their “bals” to sign me up as the fifth member of the orchestra. The owner was delighted with the idea of having me join and play both the accordion and keyboards but, alas… he couldn’t afford to pay for an extra musician (how surprising!) As I truly wanted to play, I offered to do it for free—and I didn’t regret it. Little by little, many changes took place in the orchestra. First, lead guitarist Paul Benoît left and was replaced by Daniel “Asta” Aizier. As Asta had different musical tastes, he steered the band away from 1960s blues, pushing for a playlist that included more radio hits. As French variety was starting to get more interesting at that time, we also started playing more songs by French bands. And then, Gérard Salvati left. It was now only the four of us: the Corbont brothers, Asta, and me. I started to get paid. And it lasted in that form until December 31, 1979. During those years, I also learned to play new instruments, such as the bass and the drums. Depending on the songs, we had to change instruments for one reason or the other. While I never played the drums on stage, I had a lot of fun in the practice room.

Tell me about writing ‘Christelle ou la découverte du mal’ and the concept/vision you had for this when approaching the guys in the band in ‘79.

On February 28, 1975, I went to Colmar and attended the show that would forever change my life as a musician: Genesis, on the European leg of their “The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway Tour.” It was fantastic! The music, the lights, the special effects, the acting of Peter Gabriel—I liked everything. And projecting those slides on the 3 screens at the back of the stage was brilliant! I came out of there thinking that was what I wanted to do: telling a story in words and music, on a background of slides. From that moment on, it was constantly on the back of my mind, and I tried to come up with a story. I was very fond of my second cousin Christelle, who was 5 years old at the time. She was a lovely little girl, full of life, joy, and vitality, full of the laughter we shared whenever we were together. I decided to make her the heroine of my future creation—now, onto the story. While frolicking in the countryside, the little girl suddenly meets a Genii who makes her have terrible hallucinations. She discovers that the world around her is much less calm and kind than she previously believed; a sort of accelerated life training in a way! When she gathers her wits, the Genii tells her that a worldwide nuclear war is about to happen, before disappearing in a cloud of smoke. War indeed starts, and it is made clear that Christelle will die in the fallout. Wow! I grabbed a spiral notebook and started to write my story, writing it as it came to me in the summer of 1976. I still had to work on the songs, and that part took me quite a while. I owned a home organ, a Yamaha CSY-2. It had a double keyboard and a pedalboard; I used it to compose most of the titles of my rock opera. I came across one specific flute sound that I absolutely wanted to use in the Overture, the opening theme that introduced the world of little Christelle.

There was also a sound that was totally new to me, and probably to many people at the time: it was called “trumute.” It sounded weird and modulated a lot, like a wah-wah pedal. Using that mesmerizing sound, I played an E, then a D, a C, then again a D, before returning to E—I now had the atmosphere for the theme of the Genii. I’ve often heard experts claiming that the sound came from a Moog synthesizer. Ha, sorry guys! It was my good old CSY-2 and its trumute. I went on to imagine and compose the different themes of Christelle’s hallucinations and also the Genii’s departure. The rather long war theme was composed much later, after we had started the actual rehearsals with the band. Before going any further, I’d like to talk about the way I was doing multitrack recording to start designing the future arrangements for the songs. I owned a small Phillips EL-3302 tape recorder (known as Phillips K7 in Western Europe). A friend of mine had a similar device; for the sake of this explanation, we’ll call them tape A and tape B. So I would play a theme X and record it on tape A. Then I would start recording on tape B, play theme X on the speaker of tape A, and at the same time play theme Y. The result is themes X and Y on tape B. I would then repeat the process one more time in order to record theme Z. At that point, I would be able to listen to the mix of the three themes X, Y, and Z on tape A. I typically didn’t go any further as it started to get messy after superimposing three “tracks” using my homebrew method. To those of you wondering why I did not simply use a data acquisition device connected to a computer, please bear in mind that in 1976/1977 we couldn’t even fathom that sort of technology existing at any point in the future! While analog multitrack systems had obviously existed for decades, I didn’t even consider it an option as their price range placed them way beyond my reach. It turns out I wouldn’t be able to record correct demos until 1983, when I purchased a 4-track TEAC3440. Armed with my rotten tapes, I started looking for the musicians who would follow me on my great adventure!

Most of the guys in Secession were older than you, correct? What initially led to Rictus forming around this time in ‘81? Did a lot of the guys from Secession end up coming over to help form Rictus?

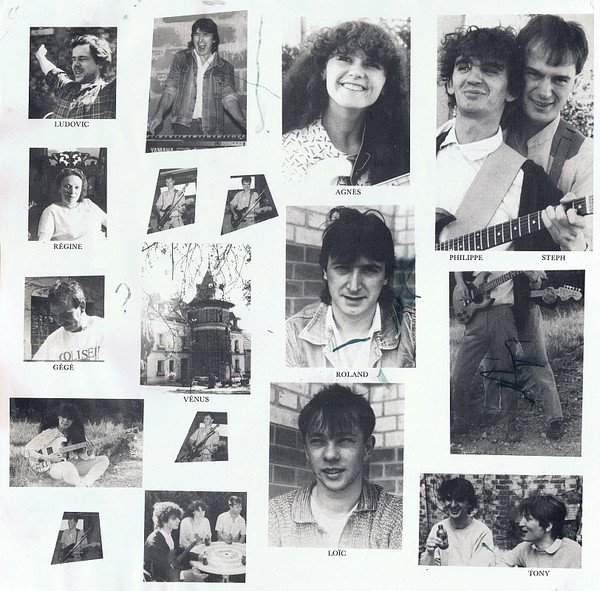

Composing the music on my little tape recorders took me a long time. I think I didn’t start talking to people about my project until late 1977, maybe early 1978 even. I wanted to call the new band Rictus; it was a name that had stuck with me as I was leafing through a dictionary. If you peruse some of my past interviews, you might spot me claiming it was an acronym for “rock initialement cosmique transcrit à usage social” (French for “cosmic rock transcribed for social use”), but that’s just something I had made up to jazz up the interviews. I just got tired of having to answer the same question again and again—I guess I also got a kick out of seeing how dumbfounded it left the interviewers. From the start, I had considered asking my bandmates from Secession to take part in the project, but now I was hesitating: as they were used to get paid for their musical endeavors, I was afraid they wouldn’t consider playing just for the sake of it. I clearly had no way to pay anybody at that point! I decided to start with Daniel Corbont. As I explained the gist of the project, I could sense his excitement. I finally asked the big question: “would you be okay to play the bass?” He replied without missing a beat: “yes, but I don’t want to sing.” No worries Daniel, that wasn’t part of the plan anyway. I now had a bass player, and a good one at that! Then I went to Asta, who also accepted to join us. François Corbont, Daniel’s brother, felt uneasy with how ambitious the project was; he’d eventually join us, but later on. Around that time I met Claude Marchadour, who was the guitarist and composer for a band called Smog. Attending their rehearsals, I start to notice that the atmosphere was quickly deteriorating, mainly due to tensions between Claude and his drummer. The clash was unavoidable: one day, a huge row broke out between them two. I remember seeing the drummer dropping his drumsticks angrily and basically quitting on the spot. That was the perfect opportunity for me to hire him! His name was Pierre Pomet; a gruff little guy who was very much into jazz-rock. I still needed a singer: I placed a classified ad in the local newspaper, stating that I was “looking for a loudmouth singer for an opera-rock project in the Luxeuil area.” A few days later someone rings my doorbell: “Hello, this is the loudmouth singer.” His name was Jean-Claude Schmidt and he lived in Raddon, a small village nearby. He was a character; sporty and cultured, active at the town’s youth center, politically committed and defending progressive ideas. He was also singing in a small “bal” orchestra called ONESYME, which was known for their covers of Rolling Stones, Beatles, and protest songs in French.

When and where did the group first rehearse? What was the chemistry between everyone like right off the bat?

We first started rehearsing in the soundproofed room used by Claude Marchadour’s band Smog. Claude had set up a rehearsal room on a farm in the village of Ormoiche; you could play at any time of the day or night without disturbing anybody. Unfortunately, not too long after we started, Claude had to leave the region and we had no choice but to look for another place. We were then allowed to use the first floor of the town hall of Servigney, an even smaller village. As the room wasn’t acoustically treated, it was absolute hell: after playing in there, our ears were badly ringing, and we were truly running the risk of going deaf. Thankfully, we didn’t have to endure it for very long. A few weeks later, our singer Jean-Claude Schmidt obtained the green light to rehearse at the youth center of his village, Raddon. But I had had a new idea in the back of my head since I had attended another Genesis concert in Colmar in 1977; it was the “Wind & Wuthering” tour with Phil Collins as the lead singer. There were two drumkits on stage, one for Phil Collins and the other for Chester Thompson. Two drummers on stage, I wanted that too! So I went back to François Corbont of Secession and asked if he had changed his mind and would now accept to join the band. I was delighted to hear him say yes—he had actually been dying to play with us since attending one of our first rehearsals! What brought us together was our desire to bring the original project to completion. None of us had attempted to create their own music until then; while everyone was experienced when it came to playing with a band, it had only been to play covers. The guys I hired had to trust the youngster I was. I think I was lucky that they did, considering I had never done anything like that before. I guess I’m one of those nutsos who wake up one morning with a dream, a revelation and set off to reach that very specific goal, spreading their enthusiasm and excitement to those around them.

Tell me about writing as well as recording the songs that are featured on the band’s debut LP “Christelle ou la découverte du mal”.

When rehearsals started, a good chunk of the themes had already been composed and written (with the help of my two Phillips tape recorder.) As Pierre Pomet also had skills as a composer, we worked together to create the “Theme of Drugs” and “Flashes.” We brought the whole “Theme of War” to life all together in the rehearsal room, building up on the ideas I was bringing to the table, organically expanding them. The progressive creation of the “Theme of War” was undoubtedly the most interesting part of the whole project. The “Theme of War” is a 15-minute piece made up of seven different sections. I would bring a new basic idea to the rehearsal and play it on my Fender Rhodes, allowing everybody to organically add their own part to it. By the end of each rehearsal session, we were able to come up with a new section. The only issue was that we had no way to keep track of our findings, as we weren’t recording anything and nobody was taking any notes. We would start the next rehearsal having forgotten massive chunks of what we had built together in the previous sessions—or in some cases, we wouldn’t agree on what had been decided previously! We ended up spending a big portion of each session trying to remember what had been done, leading us to waste quite a lot of time. I remember we felt really annoyed by all of that at the time, all of those months wasted. Today, it just makes me laugh, as I don’t see the passing of time the same way.

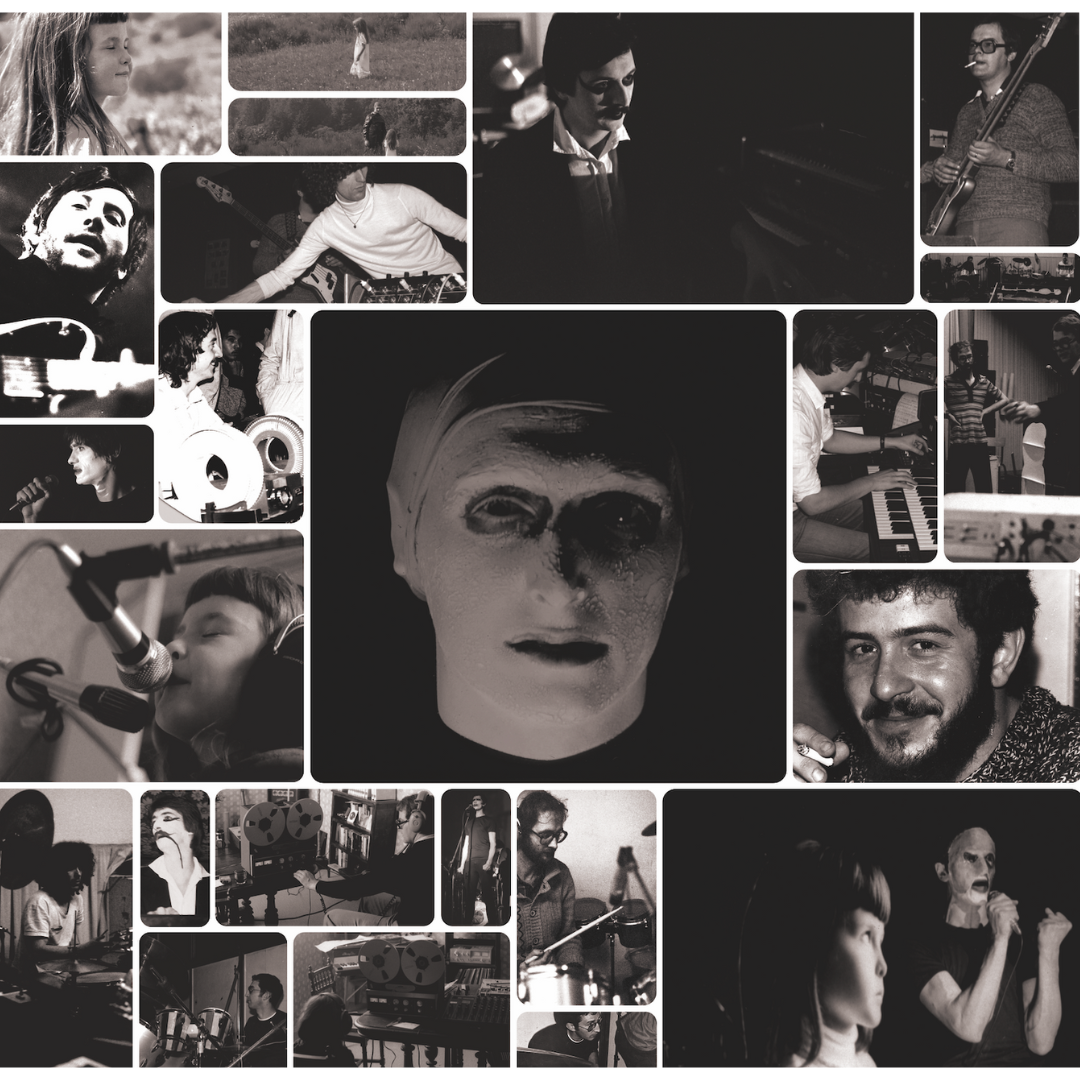

There’s no real “wasted” time when working on music. Nevertheless, if there’s something that such an experience taught me, it is the importance of carefully structuring artistic projects—something I made a point of doing, with increasing care and precision, over the following decades. Going back to Christelle, at some point Daniel started bringing his Revox tape deck to rehearsal, and the problem was solved. At some point in 1979 I met painter and photographer Guy Mauvais. He quickly got in charge of the visual part of the future show, i.e. the slides projected behind the musicians on stage. The slides were meant to illustrate each musical theme; in them, I play the Genii. All the band members play a role (the policeman, the blind man, the brawler, Prosper the bastard, the drug addicts), and little Christelle dons the eponymous role. She didn’t have to play or pretend much, and just had to be herself. She wasn’t truly intimidated during her encounters with the Genii, since I was playing the character and we loved each other. I have very fond memories of the laughs we had! We were rehearsing on a regular basis, but never really talked about going on stage. There’s no doubt it scared us a little and if I happened to bring up the topic, I was immediately put down by some of my fellow band members who claimed we weren’t ready for it yet.

The status-quo was preserved until I couldn’t take it any more: one morning, I woke up and knew it was the right time to make things happen. We had to set a date and get ready for the big night. I was quickly able to convince Daniel, who helped me devise a strategy: “we shouldn’t give the others any choice!” We started looking for a venue and found one. It was the movie theater in the village of Fougerolles, 5 miles away from Luxeuil. It was an old-style concert hall, with a large stage and a seating capacity of around 300. At the next rehearsal, we announced that the first concert of Rictus would take place on July 18, 1980. Some of the musicians turned pale and you could see the fear in their eyes, but they couldn’t change my mind now. It was January 1980 and we had 6 months to organize everything—everything. We had the venue, but nothing else! On the musical side, Asta invited me to hire a second guitarist to support him. I didn’t think it was truly necessary, but I understood it would help him feel more confident on stage, so I let him bring in one of his friends: Marcel Bony. However, Marcel ended up leaving after the first concert, leading us to rewrite the arrangements for a single guitar.

As to the first show in Fougerolles, I would like to quote here what Jason Connoy wrote on the cover of the 2012 reissue of Christelle:

“We used the same sound system as we had been using with "Secession", a humble but capable setup. This also saw the introduction of Agnes Brice, a young woman who met the band through her ability to work the lighting during the show. This aspiring bass player would eventually join Rictus two years later, and has remained the Rictus bass player until today. […]The show was played seven times in total in small surrounding towns. It wasn't easy to find places to play, especially for an unknown band that saw no support from radio or television. Apart from some small write-ups in local newspapers, Rictus’ name was spread by word of mouth.”

When and where did recording begin in ‘81 and what was that process like creating those songs? How did the deal with Le Kiosque d’Orphee come about?

Once again, I’d like to quote what Jason wrote about the recording process and our deal with Le Kiosque d’Orphée:

“At the start of 1981, Guy Mauvais suggested the band make a record. With no label and no money, the idea seemed more like a fantasy then a reality. Luckily a small pressing plant named Kiosque D'Orphee had been opening doors for local talent.

Roland discovered "Le Kiosque D'Orphee" through an advertisement in "Rock & Folk", a French music magazine. They were a small pressing plant based in Paris that would press small quantities of vinyl for anyone who could supply a master. They didn't offer any distribution or contracts, just a means for smaller bands to press vinyl. Rictus recorded their debut using an AKAI 4 tracks owned by one of Roland’s friends, Francis Paul. The band played live, just like on stage. They started by recording a 2 channel stereo recording of the entire project. The following week the vocals were recorded on the third track, and finally the fourth track was used for guitar and keyboard solos. The final mix was bounced down to a Revox B77 a week or so after recording the final part of the album, the poem by Christelle. The tape was then sent to "Le Kiosque D'Orphee" for pressing.

"Le Kiosque D'Orphee" also offered cover printing, but at a fairly high price. This is most likely why some of the releases on the label resorted to paste on covers. In the case of Rictus, they decided to try making the covers themselves with the help of a local print shop. The folding, cutting and glueing of the covers was all done by the band at home, and the artwork was designed and created by Guy Mauvais. The press was limited to 250 copies, most of which were sold to friends, family and fans of Rictus. Distribution was limited to a small record shop that took on sales to help the band.”

What was the first order of business once the album was released? Did you guys go on tour, or play a line of shows to help promote it? The band would go on to record throughout the rest of the 80’s and 90’s. When you reflect back on those early days in Rictus, what are you most proud of?

No, no new tour was organized following the release of the record. A certain weariness had undoubtedly set in for some of us, but we tried to make it work for a while. We recorded a single (“Mécanique”) a few months later before going on a hiatus to give everybody the time and space to decide if they wanted to keep playing. We ended up disbanding at the beginning of 1982. After a few months feeling down, I decided to build a new Rictus with different musicians; that’s the time when bassist Agnès Brice joined the band, and she’s been a part of it to this day. What am I proud of? To tell you the truth, at the time I wasn’t proud of anything considering the relative lack of success of that whole “Christelle” experience. I quickly moved on to something else! My musical style evolved, and I played rock, pop, and chanson, leading to a certain degree of popularity at the local level. Until a few years ago, I hardly ever mentioned “Christelle” in interviews. Now, I’m 68 and if I look back on my musical career, the only work of mine that is known and discussed all over the word is my “Christelle”—the one we recorded on a 4-track tape recorder at a youth center! In 2011, I received an email from Toronto. Jason Connoy was asking me if I was interested in reissuing “Christelle.” It’s truly at that moment that I realized that the record, of which only 250 copies were pressed, was quite well known in the world of progressive music lovers. Jason did a fantastic restoration job.

He used his own copy of “Christelle” to redo a master recording as the original one had never been returned to me by the Kiosque d’Orphée; in spite of my efforts, I was never able to get my hands on it. The reissue consisted in 700 freshly pressed LPs and 1000 CD copies, and it was sold all over the world. The whole experience didn’t really change anything for me: I didn’t dive back into the music I made in the 1980s. It was only in 2020 that I truly rediscovered that music: it was the year I decided to stage a special show to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Rictus. I felt a sense of pride listening to it again. For that special anniversary, I tried to bring together the former members of Rictus to play again “Christelle” on stage! Sadly, some of them had left us already; some others had quit music altogether. Only Daniel Corbont was able to join, playing the Fender Precision bass he was using at the time of the original series of concerts. I filled the vacant spots with new friends, including Daniel’s children Olivier (drums) and Emilie (flute.) To prepare for this concert, I went back to the roots of my music from 1980. I locked myself up in my little studio and I rediscovered the themes one by one, with increasing excitement. I was finally able to hear my music the way I had previously only been able to imagine it. I kept some of the original arrangements and rewrote some others if I felt it was necessary. It brought me a lot of joy, and that period is undoubtedly the one during which I took the most musical pleasure in my whole life. While the concert was scheduled for April 2020, it had to be postponed several times due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It eventually took place on April 30, 2022, to a packed house and to great success. We also decided to make the most of the pandemic: we recorded Christelle again, this time in English, for all our English-speaking fans. That’s how the “Christelle or the Discovery of Evil” CD was released in 2021. And now, listening to it, I feel very proud of the work done: music imagined in 1980, but finally played at it should be in 2021!

What have been up to in more recent years? Are you currently working on any new projects? Is there anything else you would like to further share with the readers?

The April 2022 concert was entirely video recorded. We’re currently working on a DVD release of the live, scheduled for early 2023. I would like to greet your readers; I have no idea how big your audience is, but I want to say hi to I would like to greet your readers; I have no idea how big your audience is, but I want to say hi to every single fan out there. Thank you for sharing this moment with me. I have recorded around ten albums during my musical career; every time I had a lot of fun and I met some great people on the way. I’ve had the luck to play with fantastic, and in some cases, with truly exceptional musicians. But the rediscovery of “Christelle” has been the most beautiful musical period of my life, and has definitely brought a sense of closure to the whole thing. I am very happy to be able to express it and share it here with people who will probably understand me.

Sincerely,

Rol Brultey

December 2022